Nuevo Leon’s Anticorruption System: Taking Stock of an Ongoing Experiment in Fighting Corruption at the Local Level

Nuevo Leon’s Anticorruption System: Taking Stock of an Ongoing Experiment in Fighting Corruption at the Local Level

Bonnie J. Palifka, Luis A. García and Beatríz Camacho

Mexico’s corruption problem seems intractable. Multiple public and private efforts have failed to reduce the pervasive role of corruption in virtually all areas of life. Indeed, despite these efforts, perceptions of corruption have worsened over the past decade.

When federal law created a National Anticorruption System and required state governments to do the same, a group of NGOs, business organizations, universities, and prominent individuals in the northern state of Nuevo Leon formed an Anticorruption Coalition, which aimed to improve upon the national system, primarily through enhanced citizen participation. Rather than confronting Congress, the Coalition worked with legislators to create a system that has gained national attention for its innovations, although it remains imperfect. We review progress so far and present the Nuevo Leon approach as a model for civil society to shape public policy by empowering local actors.

Nuevo Leon’s State Anticorruption System

President Enrique Peña Nieto entered office in 2012. Although during his campaign he had promised sweeping anticorruption reforms, this commitment took a back seat to reforms in other areas, such as energy and education. It took a major scandal in 2014, involving the first lady’s acquisition of a luxury home from a major government contractor (dubbed the ‘Casa Blanca scandal’) finally to prompt the government to act.

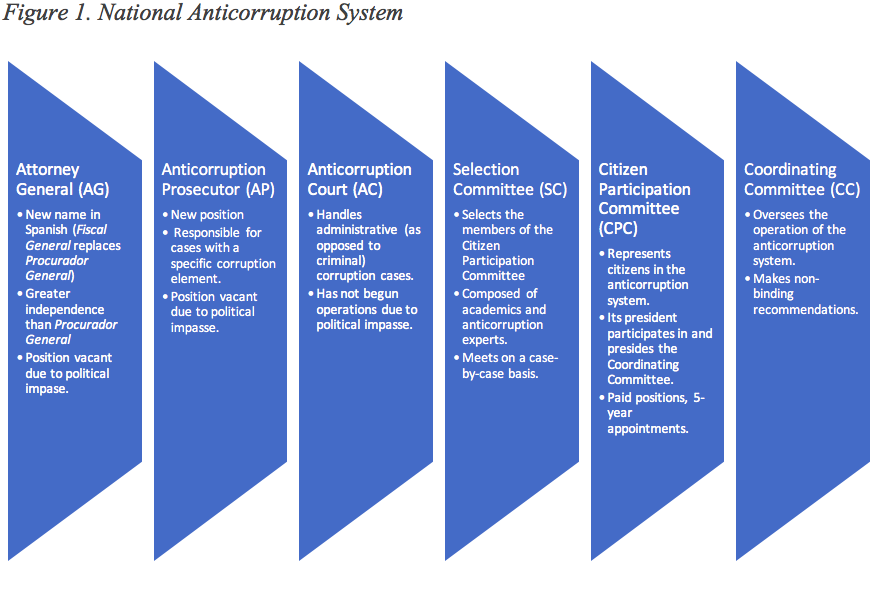

Thus was the National Anticorruption System (NAS) born. Although some critics argue that it merely pays lip service to anticorruption, the NAS incorporated major legal changes and established a series of institutions, mechanisms and rules designed to promote coordination, including data sharing, between anticorruption agencies and across states. It also required each state to implement equivalent local systems (State Anticorruption Systems, SAS) within one year. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. National Anticorruption System

In 2015, Nuevo Leon became the first state in Mexico with a politically independent governor. In this context, the Members of Congress were willing to work with civil society to prove their own legitimacy.

Nuevo Leon’s Anticorruption Coalition was formed in late 2016. Representatives of 21 stakeholders—NGOs, universities, trade organizations, and individuals—met over the course of six weeks to plan and establish goals and roles, and on 7 October held a press conference to announce its formation and objectives. On 18 October the Coalition presented the local Congress with a list of key points required to achieve its vision of ‘the best anticorruption system in Mexico’.

Over the next five months, the Coalition developed and followed a series of strategies to achieve its aims, including:

- Bi-weekly Coalition meetings, at which the constitutional changes were discussed in detail and a series of proposals were prepared to share with Congress.

- Public meetings, which were organized with a set of thematic tables of 8-10 people each. Citizens were invited to propose ideas on specific aspects of the local system.

- Presentation of proposals. Coalition members held meetings with members of Congress to explain and discuss the proposals.

- Publicity and transparency. The proposals and results were represented in colorful diagrams and shared on a website, Facebook, Twitter, and other social media. Members of the Coalition also participated in press conferences, gave interviews, and wrote editorials.

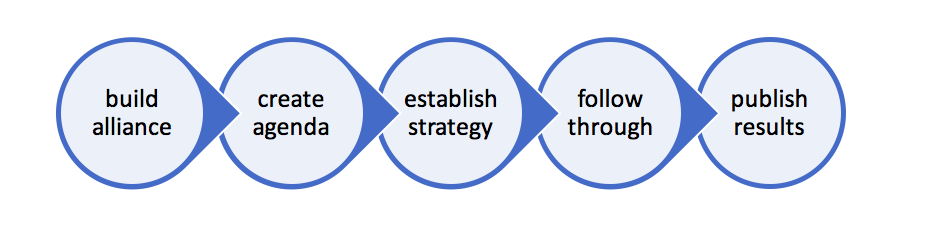

The Coalition’s process can be illustrated in five steps (Figure 2).

Figure 2. How the Anticorruption Coalition worked with Congress

Accomplishments

The Constitutional reforms were approved on 9 March 2017. The Coalition’s efforts led to several notable achievements that went above and beyond the requirements of federal law, including:

- Public processes for submission of candidacies, interviews, and selection of all major anticorruption authorities.

- The creation of an ad hoc Selection Committee to ensure citizen participation in the selection processes.

- Formal, budgetary, and operational independence of the attorney general, the specialized anticorruption prosecutor, the state comptroller, and the specialized anticorruption court.

- Greater citizen participation in the Coordination Committee, the system’s main governing body, as well as making its decisions legally binding.

- Additional mechanisms to prevent, detect and punish corruption, such as:

- elimination of prosecutorial immunity for elected officials

- increased statutes of limitation (from 3 to 10 years) for corruption-related crimes

- enhanced whistleblower protections

- stronger asset-recovery faculties

- improved audit and investigatory powers

- penalties for individuals and firms implicated in corrupt acts

- inferred responsibility of superiors

The citizen response process has been extraordinary. Despite tight deadlines and time-consuming requirements, numerous qualified candidates applied for each position. The Selection Committee was appointed by Congress with the assistance of a legally-mandated body of citizens, which published a methodology to evaluate applicants and issued a ranking of finalists, considering individual merit, diversity, expertise, and team cohesion. Likewise, the Selection Committee interviewed and evaluated the candidates for Attorney General, Anticorruption Attorney, and magistrates, and these positions have been filled.

Lessons learned

Although much was accomplished, there are several ways in which this process could be improved. First, despite some efforts, the Coalition did not engage directly with the governor, which further estranged him from the process. As a result, he opposed several parts of the proposal. For example, he wanted the Attorney General to be elected by popular vote.

Second, some of the requirements for candidates are excessive, especially considering that deadlines are usually two weeks from the publication of the call for applicants.

Third, the Coalition underestimated the politicization of the process during the implementation stage. Rather than voting as individuals, Congress voted en bloc with no discernible selection criteria, despite the rankings they received. In some cases, Congress chose—almost unanimously, suggesting political pressure—candidates who had alleged connections to political parties.

Fourth, the Selection Committee deviated from expected behavior in several ways. One member stepped down, resulting in a legal controversy. The Committee refused to exclude any applicants for Attorney General or Anticorruption Prosecutor, despite clear conflicts of interest in several cases. As a result, Congress was free to choose the finalists from the entire applicant pool. Furthermore, the Committee did not publish its methodology or ranking of candidates.

Fifth, the Coalition did not set realistic long-term goals or timelines, failing to anticipate that the process would be interrupted during the electoral season.

There are two additional positive lessons: (1) the separation of powers enabled Congress to make laws that would create autonomous bodies to act as a check on the government; and (2) the diversity of expertise within the Coalition enriched the discussion and formulation of the proposals.

Conclusions

Nuevo Leon does have an exemplary State Anticorruption System, but over a year after the law went into effect, the System is still incomplete: the Citizen Participation Committee has yet to be created and the Coordinating Committee cannot convene until then. It remains to be seen whether that selection process will be more transparent and less politicized. In addition, a series of complementary laws covering specific subjects must be debated; this process has stalled due to impending elections.

Despite its shortcomings, we believe the Nuevo Leon model provides useful lessons in setting up or improving an anticorruption system. By coordinating the efforts of several stakeholders, the Nuevo Leon Anticorruption Coalition was able to promote a cohesive, comprehensive vision. Establishing clear and broad objectives from the beginning, engaging in constructive dialogue, and embedding citizen participation throughout the process, seem to have yielded mostly positive results.

Bonnie J. Palifka is an Associate Professor of Economics at the Tecnológico de Monterrey.

Luis A. Garcia is a practicing attorney specializing in corporate compliance and anti-corruption matters.

Beatriz Camacho is an activist for civil participation in public affairs, especially on governmental transparency, access to information and electoral observation.

All of the authors are members of Citizens Against Corruption, a founding organization of the Anticorruption Coalition.