Every Penny Counts: Exploring Initial Strategies for Successful Open Contracting Initiatives in Challenging Environments

Every Penny Counts: Exploring Initial Strategies for Successful Open Contracting Initiatives in Challenging Environments

Tom Wright, with Eliza Hovey and Sarah Steingruber

Open contracting is the practice of publishing and using accessible information throughout the procurement cycle to ensure that public money is spent honestly, fairly, and effectively. The Open Contracting approach aims to boost the integrity, fairness and efficiency of public contracting.

While the concept of open contracting is not new, innovative technologies and approaches such as e-procurement, smart technologies and the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) have started to unlock its anti-corruption potential in new and exciting ways. Data is more interoperable and effective, easier to access, visualise and use.

These breakthroughs allow for more and better analysis which can, for example, reveal patterns and anomalies and, over time, uncover corrupt practices such as kickbacks and collusion. The anti-corruption value of open contracting lies in its ability to make systems more transparent and accountable.

Open Contracting: The New and Improved Anti-Corruption Tool

This blog explores how the impact of open contracting can be realized and sustained in contexts that may lack the most optimal institutional and technological arrangements.

It is based on initial evidence generated by Open Contracting for Health (OC4H), a DFID funded, 3.5-year multi-country project which aims to facilitate the implementation of open contracting in the health sector. The project is currently at the beginning stages in Uganda, Zambia and Ghana.

Here, we present an “exemplar” open contracting case study from Ukraine which is based on the “ProZorro” system. This example serves as a touchstone to explore three particular challenges:

- Securing commitment from government stakeholders and civil society

- Managing differences in technological capacities

- Engaging with the private sector

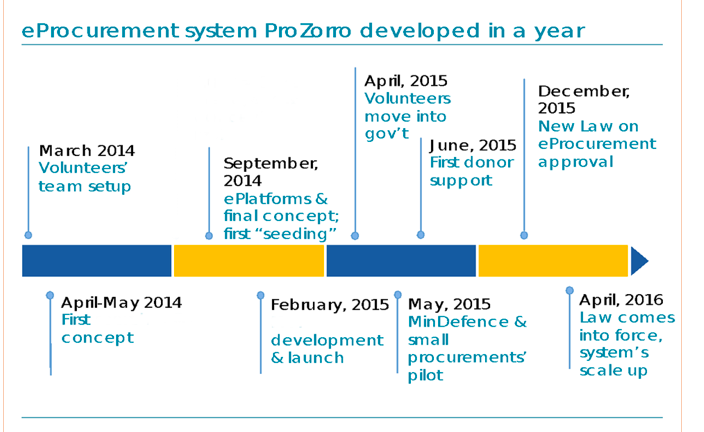

ProZorro: An exemplar case

ProZorro is Ukraine’s public e-procurement system, designed to enable public access to procurement data in easy and innovative ways. It uses the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) to record all public procurements while employing the mantra of “everyone can see everything”. Two characteristics in particular make ProZorro unique:

- All information related to the tender process, including suppliers’ offers, can be accessed and monitored by anyone.

- Key actors each have a clear role in the “golden triangle”: government actors are accountable for setting the rules; businesses provide services to contracting authorities and suppliers; and civil society monitors procurements. This style of cooperation has significantly improved trust among all key stakeholders.

While anti-corruption effects are hard to quantify, real-time information is consistently used by NGOs and the investigatory media, indicating that ProZorro is actively assisting the government to become more transparent and accountable. Such engagement led directly to the uncovering of several procurement scandals, including the purchase of mops for £75 each which became the basis for a national advocacy campaign.

Sourced and adapted from: ProZorro: Professionalization of Procurement Function, 2016

Challenges and opportunities

- Securing commitment from government stakeholders and civil society

First developed and conceptualised in 2014 in the context of the Euromaidan protests in Kiev, the adoption of ProZorro was possible due to a unique set of circumstances. Essentially, citizens lost all confidence in the government’s ability to manage public funds, thereby providing front line civil society organisations and transparency activists both the opportunity and the means to implement the ambitious project that became ProZorro.

Strong buy-in from government and wider civil society has been identified as the key reason as to why ProZorro was so successful. However, the uniqueness of the Ukrainian context means that similar commitment is unlikely in OC4H’s target countries. Therefore, the question must be asked: how do we achieve comparable engagement in Uganda, Zambia and Ghana?

In our experience there is no single silver bullet, but instead a range of different strategies and approaches is needed to maximise buy-in.

One such approach is the development of a robust ‘use-case’. A use-case is defined by the needs and wants of local stakeholders; for example, in Ukraine the use-case “more competition in procurement” was identified as important for all stakeholders. The use-case approach localises the project and ensures that people are empowered to make decisions on how open contracting should be implemented.

This is trickier than it may seem: while diverse sets of stakeholders may see value in thematically similar themes, we have found it difficult to package and communicate these in a way that works operationally for all groups. The major learning for us here was to adapt the scope of the project to match the particular aims and resources, whilst always emphasising a strong and localised use-case. In Uganda, for example, OC4H has narrowed the scope of the project to one or two institutions based on our scoping studies.

- Managing differences in technological capacities

ProZorro is a technologically sophisticated platform that utilises a variety of tools and attracts a lot of public attention. This includes the citizen monitoring platform, a business intelligence tool, and a tool for identifying corruption risks. Each month, around 200,000 Ukrainians search for ProZorro or related keywords on Google. It is clear that key to the success of ProZorro is the technological development of the platform allied to the country’s technological capacity.

Our project operates in countries that do not have this technological environment. Only 22% of Uganda’s population regularly uses the Internet and most health ministries have limited technical capacity and lack sufficient specialists to assist in implementation and management.

However, such blanket assumptions ignore pockets and trends of high capacity and technology use that can be harnessed. For example, smart technologies, e-procurement and mobile data are rapidly becoming popular in our target countries. We aim to use smartphone applications for our training programmes and to adapt data tools from other countries to the specific context in which we will be operating.

- Engaging with the private sector

ProZorro has been praised for how it has managed to incentivise businesses to commit to the system. Hundreds of businesses use ProZorro every year, with procurement competition increasing by 50%. This is largely due to government leading businesses by the nose: procurement laws were changed to ensure that private business must use the ProZorro system. Since then, evidence of the value of open contracting has sustained the involvement of the private sector, with a survey of two hundred companies finding that 80% of companies said that the new system positively impacted their business.

Again, it is unlikely that our work will be able to ride on such political will. Our approach thus far has been to use evidence generated by ProZorro and the Nigerian system, Budeshi[1]. Our impact in this area has however been limited to date and the wins we have had are not attributable to our activities. This is an area that needs more research and a better understanding of private sector motivations.

Discussion and conclusion

The above three areas represent challenges we have faced in the countries in which we are implementing OC4H. These are meant to catalyse discussion and raise awareness of how we have tried to sustain the anti-corruption value of open contracting in challenging environments. More research is needed in all three of these areas and solutions will be very different for projects of differing scales. However, there are some lessons that can be applied generally:

- The ‘use-case’ is of critical importance. Success of open contracting is based on achieving the needs and wants of the stakeholders and so do not dilute the use-case’s significance by widening the scope of a project past what its resources can achieve.

- Smaller scale, narrower scope projects can be impactful and serve as evidence for advocating further open contracting work.

- Open contracting implementation should be an inclusive process where project staff sustain constant dialogue with local stakeholders.

- There is still a lot more to understand, especially in terms of how to utilise the changing technological landscape of low and middle income countries and how to engage the private sector.

One size does not fit all – the situations that led to the success of ProZorro are unlikely to be replicated elsewhere. Therefore, different opportunities will need to be seized and challenges circumvented.

Tom Wright is Research and Advocacy Officer at Open Contracting for Health (OC4H).

Eliza Hovey is Senior Grants and Reporting Officer, OC4H.

Sarah Steingruber is TI Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Programme Manager.

[1] Budeshi (which is Hausa for “Open it”) links budget and procurement data to various public services. It is accessible to the public to use and analyse. Budeshi has successfully been operating in Nigeria for over two years now.